Young start-ups often have a large number of tasks and at the same time very few hands and minds to handle them. For example, smaller startups with fewer than 15 employees often have no dedicated support functions such as back office staff to take care of office organization, bookings, invoices, etc. This is often the responsibility of the founders and sometimes the first employees. At the same time, the few people who are burdened with additional tasks have to perform the most important task, namely problem validation and customer discovery. The enormous share of the later success of the company that the first employees are responsible for can be guessed from the fact that, according to a study, start-ups where one of the founders died prematurely recorded a 22% drop in productivity (https://www.nber.org/be-20212/assessing-importance-key-personnel-startup-firms). For this reason, it is important for early-stage founders to carefully weigh up whether the startup can be well advanced with the first hires. In the following, I would like to share some experiences and thoughts derived from them:

Conways Law

Most people who have dealt with software development are probably familiar with Conway’s Law:

“Any organization that designs a system (defined broadly) will produce a design whose structure is a copy of the organization’s communication structure.”

The idea is that the architecture of the software is reflected by the team structure. This is irrelevant in the initial phase because often with fewer than 15 employees, no distinct team structures are in place. Nevertheless, this transition should be considered in advance when selecting applicants for a position. For example, our experience has shown that the first 10 employees often proactively seek an environment in which informal structures exist, ideas can be quickly introduced and implemented, and in which they also have a disproportionately large influence compared to organizations with more employees and more pronounced structures. As the company grew, problems arose not only when the first teams were formed, but also when the profiles of individual employees became more pronounced. Interesting tasks have been partially eliminated here. Although the transition was partly shaped by the employees and there were opportunities for participation, there was considerable resistance to changing the status quo and even to hiring new team members. For this reason, it is important when hiring new employees to not only check whether the applicant fits into the current team, but also whether the applicant is willing to accompany the growth of the company. For us, a strong interest in the problem the startup is dealing with was a clear indicator of this. A strong counter-indicator was a strong desire for freedom and independence. While this was very positive for us in the initial phase, as problems were tackled quickly and creatively, it often led to conflicts afterwards as soon as new structures and processes were introduced. Platforms like 16Personalities, which offer appropriate tests to better understand candidates, helped us here (https://www.16personalities.com/).

Understanding Communication Complexity in Growing Startup Teams

As described in the previous section, the complexity of communication channels increases with team size. I would like to explain how we have perceived this increase:

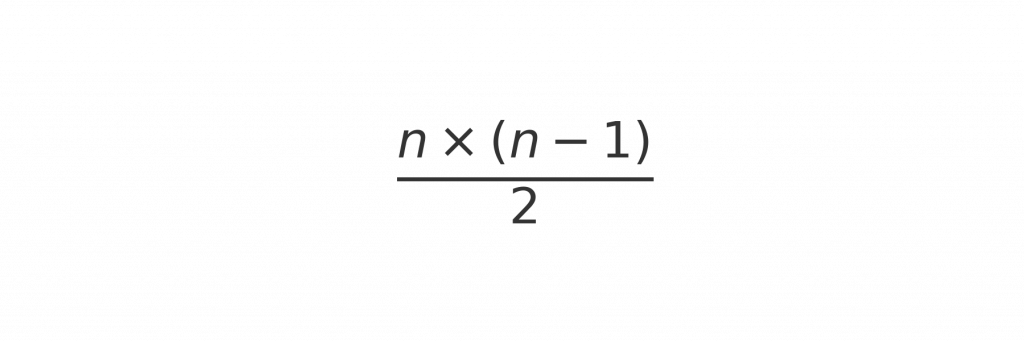

In early-stage startups, communication is straightforward when the team is small. However, as new members join, the number of communication paths increases exponentially, making coordination increasingly difficult. This effect can be explained using the following formula:

where n represents the number of people in the team. This formula calculates the total number of unique one-to-one communication links within a group.

For example:

As shown, the complexity of communication grows significantly with each additional person, making structured processes and a sharpening of the roll profiles essential at certain growth stages. We have experienced four key thresholds where communication shifts from fully transparent to requiring more structured coordination:

1. 5–7 People → Maximum Transparency & Direct Communication

At this stage, everyone could communicate directly, and knowledge flows naturally across the team. No formal structures are needed, and decisions are made quickly. The focus should remain on leveraging informal collaboration and agility. We tried to do this by discussing tasks with everyone in a weekly meeting. We also discussed larger projects on a monthly basis. After that, I would also prepare the transition by discussing possible processes and frameworks that could be used in the following stages. This way, familiarity with them can be built up over time and the transition is not perceived as abrupt by the team members.

2. 8–12 People → First Signs of Complexity

Challenges begin to emerge as not everyone is aware of all ongoing discussions. Without clear ownership, misalignment occured. To maintain efficiency, roles and responsibilities should be clarified, and lightweight coordination tools such as standup meetings, task management systems (Trello, Jira), and knowledge-sharing platforms (Notion, Confluence) become useful. In this phase of the company, we tried to focus the communication flows to the necessary extent by sharpening the role profiles and redistributing the tasks. Unfortunately, this met with resistance from many of the team members who were already among the first 6 employees. From their point of view, the attractiveness of the position was greatly reduced, as people who were responsible for product development, for example, were no longer as frequently involved in sales activities. Particularly in the case of team members who had shown high scores in personality tests and who showed the need to influence their environment, attempts were made to organize open majorities among the team members to ensure that no further people were hired.

3. 15–25 People → Silos Start to Form

As functional groups (Tech, Product, Sales) emerge, cross-team communication becomes harder. Not everyone can be involved in every decision, and structured meetings, internal documentation, and alignment processes become necessary. Introducing cross-team collaboration strategies and clearly defined ownership prevents inefficiencies. The interesting thing about this phase was that during the growth from 10 to 20 people, many team members who started in phase 1 or two resigned. There were also changes in the two previous phases. However, when we entered phase three, we had a large number of resignations, which were also attributed to a change in the organization and role profiles in final discussions.

4. 30–50 People → Scaling Becomes a Challenge

With over 1,200 potential communication links, unstructured interactions are no longer viable. Leadership roles must be defined, and efficient workflows must be established to prevent bottlenecks. Without structured reporting and clear communication channels, decision-making slows down. Implementing OKRs, centralized collaboration tools (Slack, Microsoft Teams), and structured meeting formats ensures alignment across teams. During this phase, we introduced a middle management level with the first team leads. At this point, it is important to note that a team lead position is quickly perceived as the next career level and there are of course only a small number of these and it is uncertain whether more will be created in the foreseeable future. For this reason, we have accompanied this with the introduction of career paths where teamlead levels are also contrasted with specialist career paths. In this way, the rush for these positions has been reduced.

Hire for character train for skill?

The first team members of a startup not only shape its success but also define the company culture and future structures. Our experience has shown that both the skill level and motivation of candidates in an early-stage startup can vary significantly. While some are highly ambitious and eager to drive the idea forward, others use the startup environment as a fresh start after struggling in previous organizations. Both types can have a profound impact on team dynamics and overall performance. This is why being selective about both character and skills is crucial. Poor performance due to a lack of skills or motivation can slow down the entire team, while a toxic high-performer can disrupt the culture and even drive valuable team members away. To mitigate these risks, we implemented a structured hiring process, including personality assessments like 16Personalities, cognitive and technical skill tests using TestGorilla, and hands-on evaluations such as role-playing and pair programming sessions. A rigorous selection process may seem time-consuming, but it pays off in building a strong and sustainable team from the start.

Leave a Reply